KAMPALA/TORORO – The National Resistance Army (NRA) captured power after five years of protracted fighting on January 26, dealt a final blow to Obote’s second government.

Today marks 33 years since the rag-tag army comprising of mostly young men in their twenties and early thirties captured Kampala in a victory that their leader and incumbent President Yoweri Museveni described as a ‘fundamental change’.

But was it really a fundamental change? As NRM and Ugandans hold celebrations in Tororo District to mark 33 years in power, Our reporter looks back at the over three decades of President Yoweri Museveni and the NRM.

When renown combant Oyite Ojok died in a plane crash in 1983, it remained a question of when and not whether the National Resistance Army (NRA) under Museveni will capture power.

Ojok’s death bred confusion in the military circles prompting a military junta on July 27, 1985 by Lt Gen Bazilio Olara Okello and Gen Tito Okello Lutwa, the latter being installed as the chairman of the ruling military council and head of state.

The Lutwa regime was weak from the start, a possible reason as to why the Museveni’s NRA was able to overrun Kampala without much ado in a short period of seven months in spite of the Nairobi Peace Accord of December 1985 that had called for an end to war and the formulation of a broad-based government to accommodate all the warring parties.

On January 25, 1986, the Lutwa regime was no more. Museveni and his NRM guerillas had captured power and announced the fall of the government the following morning of January 26, 1986.

New Dawn

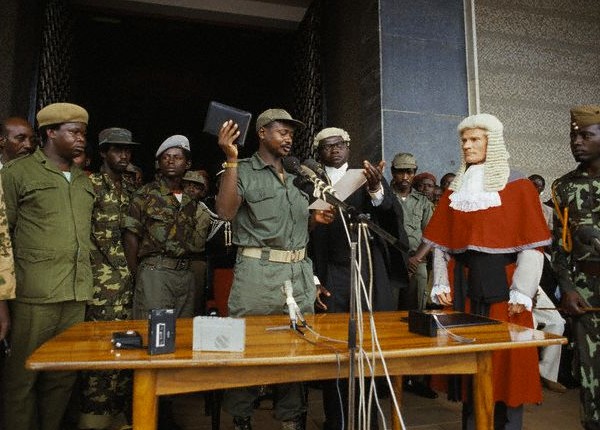

Swearing in as president on January 29, 1986, at the steps of Parliament, the revolutionary NRA/M leader Yoweri Museveni, wearing military fatigues with a brimmed army kofia blew renewed hope to Ugandans with his famous ‘fundamental change speech’.

In that speech, he assured Ugandans that he was not a mere change of guard but a fundamental change in the politics of Uganda.

In the same speech, the popular revolutionary castigated leaders who overstayed in power, and promised that he would be a transition government of only four years, after which elections would be held and power handed over to civilian democratic leadership in 1990.

Foundation for democracy

The new NRA/M regime soon embarked on the process of restoring democracy, constitutionalism and the rule of law in Uganda. The government mainstreamed the people’s committees popularly known as Resistance Councils (RCs ) through which the people would be empowered to actively participate in the decision making processes, including electing their representatives to the National Resistance Council (NRC) in 1988- the day’s parliament. Presiding over the swearing in of NRC members, Museveni was elated that he had long waited for such a measure of democracy when the people would be in charge of affairs of their country.

With the Parliament (NRC) fully restored, the next task was the national constitution. In the very year of 1988, now retired Chief Justice Benjamin Odoki was appointed to head a commission that would collect and review the people’s views that would form the bedrock for a new constitution. This was the third constitutional attempt after the 1962 (independence constitution) and the 1967 republican constitution that Obote manipulated to appropriate himself executive powers.

The search for a national constitution couldn’t be complete without the Constituent Assembly (CA) that debated and promulgated a new constitution between 1990-1995.

First ‘democratic’ elections

Following the promulgated constitution, elections were held under the Movement system (no-party-system) in which Mr Museveni offered himself up for elections. The Movement system championed individual meritocracy with the tagline of “one-man-one-vote”. Museveni contested alongside his closest rival Dr Paul Kawanga Ssemwogerere who stood on the platform of Inter-Party Alliance.

Ssemwogerere had just resigned his Minister of Internal Affairs docket in the NRM government to contest for the highest position on the land.

Museveni “won” the elections with 76 per cent of the popular vote under universal adult suffrage, and he was declared the “first democratically elected president of Uganda”. Five years later in 2001, Ugandans would again go to the polls, with Museveni facing a surprising and unexpected rival, Dr Kizza Besigye who had just broken ranks with his commander-in-chief and declared his intentions to run for the presidency under the Reform Agenda platform.

Besigye had castigated his boss and the NRM through a loaded dossier of being “dictatorial” and diverting from the ideas from which they (NRA/M) fought in the bush.

Museveni ‘won’ the unrestive elections characterised by massive rigging, torture, harassment and intimidation of opposition supporters, and among other irregularities as cited by the Supreme Court.

Tainted legacy

Uganda has gone through three other election cycles from 2006, 2011 and 2016 general elections where again Museveni and the NRM have come under stinging criticism from the opposition and the international community over the same concerns of intolerance to the opposition, violation of fundamental human rights including the right to peaceful assembly and demonstration, expression, free media and among others.

The Museveni regime came under international spotlight on the heels of the February 2011 elections when the opposition and civil society mounted a spirited protest dubbed “walk-to-work” against hyperinflation that had pitched 31 per cent in November 2011, killer bank interest rates, high prices of essential commodities such as sugar and the regime’s dictatorial tendencies. Then came the 2016 elections that the Opposition claimed it had won and was rigged by the NRM government. Dr Besigye was also seen in a video swearing-in as president under the auspices of the so-called defiance campaign.

According to analysts, the over three decades of Museveni in power leaves him with a patched legacy as exemplified with gross corruption; extreme levels of poverty among the populations; mass unemployment; breakdown and dysfunction of state institutions; abuse of the constitution to provide for extended terms; Balkanisation of Uganda into smaller units called districts; inefficiency in the provision of public goods and services, among others. And unless something drastic is done, we are likely to see all Museveni’s good works go to nought.