Abridged from net sources

As Bernard Shaw said in his famous play; The Devil’s Disciple it is during times of chaos and hardship that man finds his true calling. The late Dr John Garang De Mabior Atem was valiant and heroic when the time came.

Born on June 23 1945 into a Dinka family of five brothers and two sisters to Mabior Atem Aruei (of the Aulian clan) and Gak Malual Kuol (of the Kongoor clan) in Buk Village Nyuak Payam, Tuic East County of Jong’lei State, Dr Garang was a very dynamic human being who wore many hats and accomplished many great feats.

Tomorrow will mark exactly 12 years since Garang, launded by many as one of Africa’s most leading sons, died in a helicopter crash on July 31, 2005 aged 60.

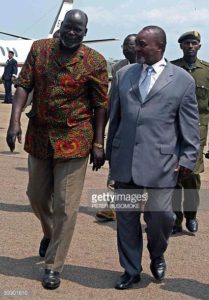

He was travelling home from a long meeting with his long-time friend, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni in Rwakitura when the Ugandan presidential helicopter aboard which he was flying crashed into “a mountain range in southern Sudan because of poor visibility” killing him and six colleagues alongside seven Ugandan crew members.

Garang’s death was a heavy blow to the painstakingly negotiated and still fragile peace agreement that ended Africa’s longest civil war just seven months before. To many, Garang’s death robbed Sudan’s marginalised non-Arab communities of a man who, even if they opposed him, stood as a symbol of dignity and hope for change.

An astute academic

Urbane and eloquent, fluent in Arabic and with an exquisite command of English, Garang was orphaned at the age of 10 and would have stayed in Bor for the rest of his life, becoming a cattle herder like his father and grandfather, had a relative not sent him to school, first in nearby Wau, then across the Nile in Rumbek.

In 1962, at the age of 17, Garang attempted to join the Anyanya I uprising in southern Sudan, but was encouraged by its leaders to continue his secondary education in Tanzania. He went on to win a scholarship to Grinnell College, in Iowa, USA and, in 1969, took a BSc in economics.

He was offered a graduate fellowship at the University of California in Berkeley, but chose to return to Tanzania as a research fellow at Dar es Salaam University. There, he met a future ally, Museveni, but was soon back in Sudan, with Anyanya.

When the Addis Ababa agreement of 1972 ended Sudan’s first civil war, many rebels, Garang among them, were incorporated into the Sudanese armed forces. After that, during 11 years as a career soldier, he rose from captain to colonel, completed an advanced course at the US army infantry school in Fort Benning, Georgia, and took a four-year break to study for an MA in agricultural economics and a PhD in economics at Iowa State University.

Joining the rebellion

On returning to Sudan in 1981, Garang found great change. President Jaafar Nimeiri, formerly close to the Communist party, was leaning towards the Islamists, who favoured the introduction of sharia law, even in the predominantly Christian south. Garang realised that the peace agreement was doomed, even before Nimeiri abrogated it in 1983 and imposed sharia throughout the country.

In May 1983, Garang was sent to his old command in Bor to quell a mutiny of 500 southern troops – commanded by officers absorbed from Anyanya – who were resisting orders to move north. He vanished. More than two months later, he reappeared in Ethiopia, where Mengistu Haile Mariam enthroned him as head of the new Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), with the rebellious Bor garrison as its nucleus.

Early military successes were followed by lengthy stalemates and crippling splits within the SPLA, often along tribal lines and exacerbated by the arrogant, authoritarian leadership of Garang and his Bor Dinka inner circle.

When Mengistu’s regime collapsed in 1991, and the SPLA lost its chief financial backer, Garang looked west, stressing the Christian character of much of the Sudanese south and Khartoum’s efforts to impose sharia upon it.

In its early years, the SPLA was, in the words of an internal critic, “a militarist instrument intolerant and averse to democratic methods and principles”, hostile to politicians and intellectuals. Many southerners were killed; others were imprisoned and tortured.

But the SPLA evolved – slowly and not always surely – from its origins as a brutal, Soviet-supported, insurgency towards a movement more genuinely representative of all Sudanese who craved Garang’s “New Sudan” – a secular, pluralist, democratic nation dominated by southerners and marginalised northerners.

Garang never deviated from his vision of the New Sudan. He knew that most southerners, even within the SPLA, wanted a separate state which they later achieved in a referendum six years after Garang’s death.

Assuming the vice-presidency

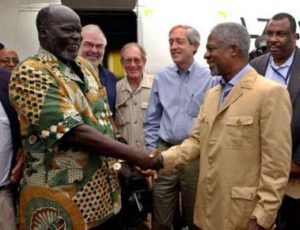

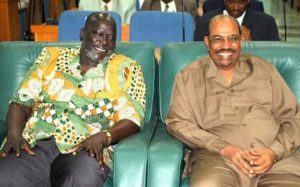

Garang refused to participate in the 1985 interim government or 1986 elections, remaining a rebel leader. However, the SPLA and government signed a peace agreement with Khartoum on January 9, 2005 in Nairobi, Kenya. On 9 July 2005, he was sworn in as vice-president, the second most powerful person in the country, following a ceremony in which he and President Omar al-Bashir signed a power-sharing constitution.

He also became the administrative head of a southern Sudan with limited autonomy for the six years before a scheduled referendum for possible secession. No Christian or southerner had ever held such a high government post.

Commenting after the ceremony, Garang stated, “I congratulate the Sudanese people, this is not my peace or the peace of al-Bashir, it is the peace of the Sudanese people.”

Assassination?

Ever since Garang signed the comprehensive peace agreement with President Omar Bashir in Nairobi on January 9, officially ending a conflict that killed at least two million people, southerners feared he would be assassinated. Peace was illusory, they said; the hardline Islamists at the core of Bashir’s regime had no intention of sharing either power or wealth.

That the first word of Garang’s death came from Bashir’s office served to harden their suspicions – even though the incident happened in southern Sudan, on a flight back from a weekend meeting with President Museveni of Uganda. But all indications to-date point to bad weather or a lack of fuel – not to sabotage.

Garang did not tell the Sudanese government that he was going to this meeting and so did not take the presidential plane. To this day nobody knows with whom Garang had met. Sudanese state television initially reported that Garang’s craft had landed safely, but Abdel Basset Sabdarat, the country’s Information Minister, went on TV hours later to deny the report.

Soon afterwards, a statement released by the office of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir confirmed that a Ugandan presidential helicopter crashed into “a mountain range in southern Sudan because of poor visibility and this resulted in the death of Dr John Garang DeMabior, six of his colleagues and seven Ugandan crew members.”

His body was flown to New Site, a southern Sudanese settlement near the scene of the crash, where former rebel fighters and civilian supporters gathered to pay their respects to Garang.

Garang’s funeral took place on August 3, 2005 in Juba.

His widow Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior promised to continue his work stating: “In our culture we say, if you kill the lion, you see what the lioness will do.”

Both the Sudanese government and the head of the SPLA blamed the weather for the accident. There are, however, enduring questions as to the truth of this, especially amongst the rank-and-file of the SPLA. Yoweri Museveni, the Ugandan president, points at the possibility of “external factors” having played a role in Garang’s death.

“When my husband died, I did not come out openly and say he was killed because I knew the consequences. At the back of my mind, I knew my husband had been assassinated,” Nyadeng added.

Those were the chilling words of Rebecca Garang, the politically very conscious widow of the late Liberation fighter.

Mrs Garang threw wide open what many had been suspecting. All the inquiries so far have ‘concluded’ that it is pilot error, bad weather, and other technical conclusions but the death was political.

So who could have done it?

Museveni said, when he went to South Sudan to pay his last respects to his fallen colleague, that the “accident” may not be what it seems.

“Some people say accident, it may be an accident, it may be something else,” he told Garang mourners. “But I assure you that if the investigation finds that it was a result of foul play, the perpetrators will pay,” Museveni was quoted as saying in another report.

Museveni also announced the formation of a panel of three experts to probe the accident. “We have also approached a certain foreign government to rule out any form of sabotage or terrorism,” he said.

Ironically, although Museveni was reportedly a long-time friend and ally of Garang, some suggest that negligence on his part contributed to Garang’s tragic demise. Then Ugandan parliamentarian Aggrey Awori told reporter William Eagle that the Ugandan government does not seem to have followed proper procedures with regard to the doomed flight.

“They took off after hours, definitely. According to CAA regulations, no rotor aircraft, [like a] helicopter, can take off after 5 pm for any destination lasting more than one hour,”he explained.

It is for precisely this kind of theorising that the Ugandan security, working on orders from on high, essentially placed a ban on further allusions to Museveni’s purported involvement in Garang’s passing.

Museveni is also reported to have directed the shutting down of a popular FM radio station after it aired a programme discussing theories about the crash, including some that blamed his Ugandan government. Mwenda who was then working as an editor at Daily Monitor, hosted then Presidential Assistant on Politics, Moses Byaruhanga, Mr Reagan Okumu, an opposition Member of Parliament and ex-intelligence chief David Pulkol, at the industrial area based KFM radio and blamed Garang’s death on the Ugandan government.