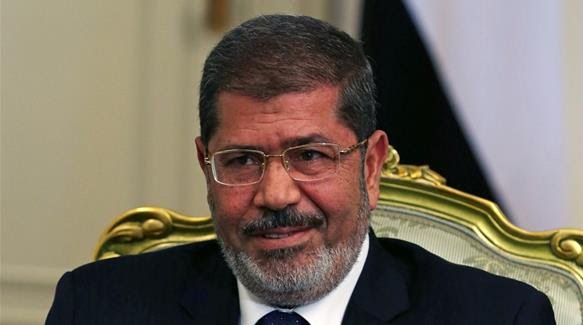

CAIRO – Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president, was buried in a closed funeral Tuesday, a day after his death inside a Cairo courtroom triggered calls for a probe into whether he had received adequate medical care in prison.

The 67-year-old Morsi was interred in a cemetery in Cairo’s eastern enclave of Nasr City, after Egyptian authorities refused to allow his family to bury him in his family’s graveyard in the Nile Delta province of Sharqiya, his son Ahmad Morsi said in a Facebook post.

The family attended funeral prayers in the mosque of the capital’s Tora prison, where they washed and shrouded his corpse and performed other traditional rites, Ahmad Morsi said. Afterword he was buried, in a ceremony only attended by family members, under heavy security.

Egyptian security agents prevented reporters and photographers from attending the funeral and barred journalists from traveling to Morsi’s village.

Morsi, a senior leader of the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood movement, was elected president in 2012, a year after Egypt’s Arab Spring uprising toppled longtime autocrat Hosni Mubarak. That vote is still considered the country’s only fairly contested presidential election and for many Egyptians, Morsi’s victory represented hope that democracy would take root after decades of military-led rule.

But within a year, Morsi had lost much of his political goodwill. Critics accused him of seeking to usurp power, mismanaging the economy and to Islamize the government and nation.

In July 2013, the military ousted Morsi after massive demonstrations erupted against his government, arresting him and other top Islamist leaders.

Morsi was held in solitary confinement for six years, largely denied access to family, friends and lawyers. His family was permitted to visit him only three times.

In calling for an investigation, Human Rights Watch Middle East and North Africa director, Sarah Leah Whitson, said that Morsi’s death “followed years of government mistreatment” and that his medical care was “inadequate.”

“At the very least, the Egyptian government committed grave abuses against Morsi by denying him prisoners’ rights that met minimum standards.”

In a statement Tuesday, Egypt’s State Information Service called the allegations a “new ethical low” and “an attempt to prematurely reach outcomes with the most politicized intentions.” It added that the accusations of medical mistreatment are “unfounded.”

A month after the military toppled Morsi, Egyptians troops raided protest camps, killing hundreds of Morsi’s supporters in Cairo’s Rabaa al-Adawiya Square and other areas. Human Rights Watch called it “one of the world’s largest killings of demonstrators in a single day in recent history.”

The Muslim Brotherhood was outlawed as a “terrorist group.”

During the coup and the massacre, the army was led by Gen. Abdel Fatah al-Sissi. He became Egypt’s president in 2014 and was reelected last year after all his credible opponents dropped because of arrest, intimidation or the lack of a level playing field.

Sissi’s government has jailed tens of thousands of Muslim Brotherhood members and supporters, all but crushing the movement. His authoritarianism has spread since 2017, silencing most forms of dissent, including shutting down hundreds of websites deemed critical and most independent media.

The government also continued to target Morsi and other top Muslim Brotherhood leaders even while they were in prison. A death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, but Morsi kept facing multiple trials for inciting violence and other charges.

When he collapsed Monday inside a glass cage where defendants are held in the courtroom, he was on trial on charges of engaging in espionage with Hamas, the Palestinian militant group.

Additional representing by Agencies