KAMPALA — Though the three-quarters of a century milestone comes at a time of many disrupted facets of international relations, experts and advocates are recognizing and celebrating the United Nations (UN) and all of its accomplishments.

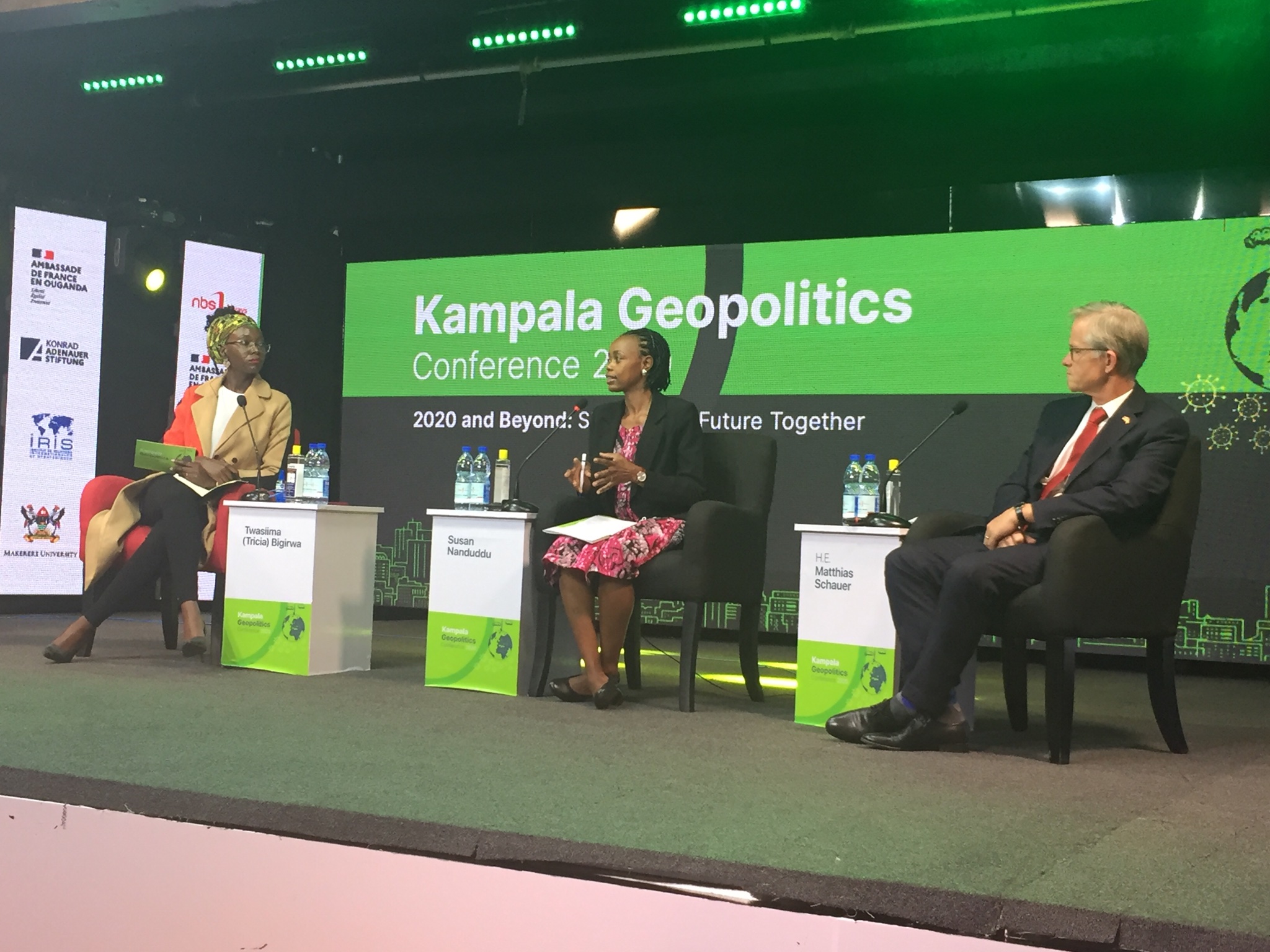

With the Covid-19 pandemic destabilizing the already-fragile balance of power at the UN and throughout the globe, the experts at Kampala Geopolitics Conference on Friday October 30 weighed in on the organization’s work and reputation — providing lucid commentary and strong opinions on the holistic actions required to address global challenges including health pandemics, climate change, income inequality and poverty.

Speaking at a panel discussion at the Kampala Geopolitics Conference,

UN Resident Coordinator to Uganda, Rosa Malango said the organization has recorded many successes in the last 75 years that are worth celebrating pointing out that: “This is the longest period of peace we have had; we haven’t had a third world war”.

“When I joined the UN 26 years ago, the discussion was about inter country wars, land mines and child soldiers. Today as we sit here we are looking at issues that affect our time; climate change, pandemics and how we can work together to find the solution,” she said.

Ms. Malango added: “There are now more UN agencies working together with the government and private sector to respond to a common goal.

H.E Matthias Schauer the German Ambassador to Uganda said that the world is changing dramatically and an upgraded UN must both adapt and stay relevant— reasoning that there is no other way of tackling issues without working together.

“We need to work together, but I think it would be good for some countries to take a step even if their neighbors haven’t, such as the banning of plastic bags,” said Mr Schauer— urging governments to support the UN as it evolves into a more agile, accountable institution, maintaining its fitness for purpose.

Along similar lines, veteran journalist Charles Onyango-Obbo urged that the cases of regional integration “we have seen during this (pandemic) period are incredible”.

“There’s is been some incredible work done,” but “I don’t think there is been sufficient global attention to it.

“This narrative of it has to go wrong in Africa has been corrected with the current pandemic. COVID19 pandemic has allowed us to reset…I am not sure we shall have a big organization like the UN; we shall have a new form of multilateralism. We shall begin to see peace and security functions becoming prominent”.

Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Uganda Country head called for a robust readjustment and e-shaping some of the institutions and rules of the game that “we have known for decades now”.

“It does not help us to apply our old concepts to the new realities, we need to understand the new realities in a new context taking into account the new interdependencies”.

On climate change, Susan Nanduddu, an environmentalist said Uganda has put in place different laws and policies to ensure a low carbon emission growth direction.

While U.N. agencies are increasingly incorporating climate change into their work, the U.N. Environment Programme remains one of the smallest U.N. agencies and had about $433 million in income in 2018. The U.N. Children’s Fund had $2.52 billion available at the end of that same year.

“Climate change is clearly the biggest challenge we face by far, but there are others, and they all interrelate in multiple ways,” Nanduddu said. The other major risk factors include pandemics and antimicrobial resistance, weapons of mass destruction, and biodiversity and ecosystem collapse.

U.N. statistics show that the number of people forcibly displaced worldwide has doubled over the past decade to 80 million. The number suffering acute hunger is expected to nearly double by year’s end to more than a quarter billion, with the first famines of the coronavirus era lurking at the world’s doorstep.

The United Nations, which has grown from 50 members 75 years ago to 193 members and a global staff of 44,000, was intended at its inception to provide a forum in which countries large and small believed they had a meaningful voice.

But its basic structure gives little real power to the main body, the General Assembly, and the most to the World War II victors — Britain, China, France, Russia and the United States — with each wielding a veto on the 15-seat Security Council as permanent members. The council is empowered to impose economic sanctions and is the only U.N. entity permitted to deploy military force.

No permanent member seems willing to alter the power structure. The outcome is chronic Security Council deadlocks on many issues, often pitting the United States against not only China and Russia but also against American allies.

It is not only on questions of war and cease-fires where the United Nations is struggling for results.