KAMPALA – Uganda remains one of the countries whose justice delivery is questioned by many citizens. This is highly attributed to challenges associated with the formal justice system which the country largely depends on.

KAMPALA – Uganda remains one of the countries whose justice delivery is questioned by many citizens. This is highly attributed to challenges associated with the formal justice system which the country largely depends on.

Many times, stakeholders especially civil society have advocated for the commitment of people-centred justice and transformation of justice systems to open up to a wider range of justice providers and to open up to innovation.

In 2019/2020 HiiL, (The Hague Institute for Innovation of Law), a civil society organisation committed to people-centred justice conducted a nationwide Justice Needs and Satisfaction Survey (JNS) in Uganda in cooperation with the Justice Law and Order Sector (JLOS). The justice needs of Ugandans have been extensively mapped, providing actionable insights on how to deliver more resolutions for increasing access to justice.

Data indicates that in 2019, 84% of the people were experiencing that they had at least one legal problem in the four years prior. The most frequently occurring problems in Uganda relate to crime (40%), domestic violence (35%), land (31%), and neighbour-related (29%).

The survey shows that almost 13 million legal problems occur each year in Uganda. Almost 70% of all legal problems do not receive a resolution or get a resolution perceived as unfair. Of those, 4.7 million legal problems are abandoned annually without fair resolution, 1.9 million are ongoing and 2.13 million are considered to be resolved unfairly.

Similar reasons triggered World Voices Uganda (WVU), a locally founded NGO that was conceived to respond to human rights violations, lack of access to justice by the poor, alarming poverty, poor health, rampant corruption and ethnic conflicts that were eating the moral and socio-political fabric of society in Uganda to engage formal justice actors on the importance of the informal justice system.

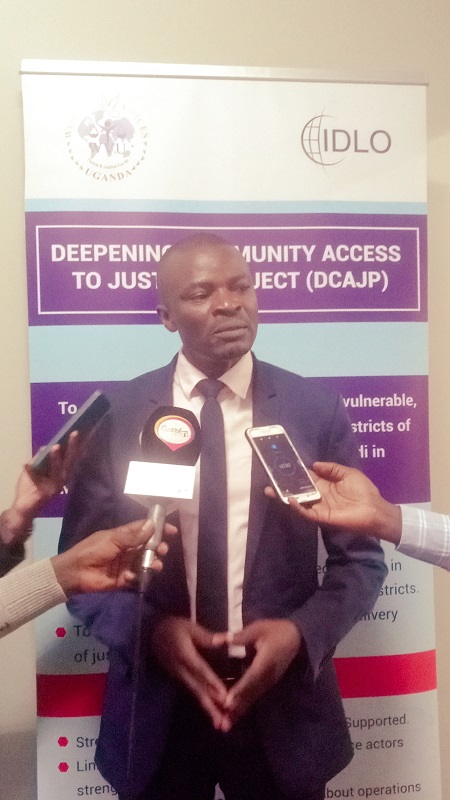

Mr. Benda Gard, Country Director, World Voices Uganda says that over time, they have learned that there are quite barriers to access to justice that most communities especially rural have been facing and as such, they have not been able to access just within the formal justice system.

Speaking at an engagement with the selected judicial officers, DPP representatives, private advocates, police, and civil society, Benda cited high costs, limited lawyers within the rural areas, the distance from the villages to courts but also the environment within the courts which is very intimidating and the language as the key barriers blocking an average Uganda to access justice within formal systems.

“Also, there has been an issue of case backlog because of many cases and justice delayed is justice denied.”

“Reports have suggested that over 80% of the cases are handled outside the formal courts. This means that the informal justice system should be the mainstream and the formal be an alternative,” he added.

According to him, there has been a misconception about the informal justice system which he says is because their contributions have not been appreciated.

“It is on this basis that we are here training the formal justice actors on the nature and operations of the informal justice system. We acknowledge the need to build the capacity of not only informal but also formal justice actors.”

Mr. Benda thinks the informal justice system should handle all civil matters which would in the end result into bigger cases. “For example, if a simple quarrel is not handled, then it can degenerate into murder.”

Mr. Patrick Ntabalo, a retired judge revealed that law tends to be very technical, complex, and expensive.

“For example, here in Kampala, an average law firm practitioner requires shs500,000 just for opening a case in the court. The average wage in Uganda especially in rural areas is shs5000 per day. So to be able to raise that money you need to save for over three years which is technically impossible because you have other priorities.”

“There has always been a quest to make justice accessible to an average person. After research in Uganda, the idea of alternative dispute resolution was mooted. The idea is that people should be permitted to resolve their disputes so long as they do it within the confines of the Constitution,” he added.

Mzee Ntabalo is optimistic that if properly practiced, the informal justice sector solves many cases fairly because it is more understandable to the average person.

Mr. Niyokwizera Emmanuel, Magistrate Grade One, Kibaale said, “To the best of my understanding, informal justice is the best mode of justice.”

He called on colleagues to appreciate that the formal and informal justice systems should complement each other for fairness in justice delivery.

“Informal is very helpful because it helps you to understand what people before you understand as justice [and] until when you understand what these people are looking for, you cannot give it to them.”

Mr. Niyokwizera noted that if recognized, informal justice will ease their work by reducing case backlog “because in the formal justice system, cases tend to be delayed for two years and above unlike in the informal where it can be disposed off in a week which saves money and time.”