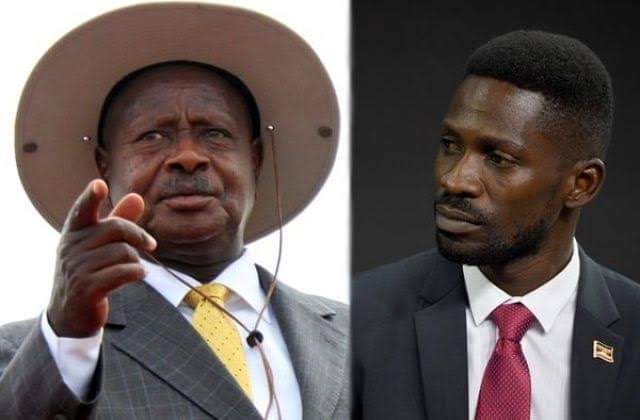

MBALE – On February 1st, 2021, the former Presidential candidate and President National Unity Platform filed his petition in the Supreme Court challenging the outcome of the 14th January Presidential election. No need to mention that prior to the Petition, Kyagulanyi had been placed under a 10 day house arrest over unjustified fears that his freedom could incite the public. It is also alleged that his phones had been disconnected and was denied access to his Lawyers to whom he would have given instructions to petition court over the outcome of the election.

In his petition, Kyagulanyi had asked court to nullify Museveni’s victory on grounds that the entire election exercise was not conducted in accordance with the laws of Uganda. Having Respondents, they filed their affidavits in reply. Before the schedule could be given, Kyagulanyi ambushed the respondents with an application to amend his first petition and cited the ground.

The Panel of 9 Justices selected to hear the petition picked up the application and invited the parties to proceed orally. These Justices included Chief Justice Alfonse Owiny Dollo, Rubby Opio Aweri, Stella Arach Amoko, Esther Kisaakye, Faith Mwondha, Paul Mugamba, Mike Chibita, Ezekiel Muhanguzi and Night Percy Tuhaise. An indepth look at the application for amendment shows that Kyagulanyi had pleaded that articles 102 (2) (b) and 219 of the Constitution barred a person holding a position of President from running for president. Note that this issue had not been pleaded in the first petition before it was served upon the respondents.

Kyagulanyi’s petition was sadly interpreted by the Respondents as an attempt to water down the contents of their reply. After submissions from both sides, the court stood over the matter for a few hours to deliver its ruling. When court resumed later that day, Justice Stella Arach Amoko who read the unanimous ruling dismissed the application on grounds that the issues the petitioner intended to add to the petition had already been included in the original petition. For me, this finding is the very reason why the application should have been granted as opposed to the argument that the application sought to introduce new matters, after all, that is the purpose for which the law allows amendments.

The Respondents had argued that the challenge of Museveni’s qualification to stand for the presidency without relinquishing his powers as president is purely a new matter and contravened the laws governing presidential election petitions that follow strict and fixed timelines which include filing the petition, service in two days, answer in three days and hearing as well as delivering the verdict within two months. They also noted that issues regarding amendments on irregularities arising from electoral processes such as during transmission of declaration result forms and the electoral offences allegedly committed by Museveni are already covered in the original petition and therefore no need to amend them.

Sadly, the law governing presidential election petitions is silent on amendments and one would be justified to say the application was time-barred due to limitation. For me irrespective of the foregoing argument, the purpose of amendment was majorly to help the court to adjudicate upon all matters in controversy and to enable the court to decide on all matters effectively and arrive at a just decision. To dismiss the application is to procure a miscarriage of justice and to block a litigant from exhausting his grievances although I personally think the Applicant should have opted to file supplementary affidavits as opposed to amendment. Similarly, the affidavit deponed by NRM’s Kihika can also be expunged during the hearing since he had no authority to do so on his behalf of Museveni, Kyagulanyi did not sue NRM as a party but Museveni as an individual, the two are not one and the same. Being the NRM candidate does not suffice.

I know that the Supreme Court has its own rules and regulations but elsewhere, the law provides that the court may, at any stage of the proceedings, allow either party to alter or amend his or her pleadings in such a manner and on such terms as may be just and all such amendments shall be made as may be necessary for the purpose of determining the real questions in controversy between the parties. Will the dismissal of the application enable court to determine the real questions in controversy? My answer is no more so that this is the supreme court of the land where an aggrieved party will have nowhere to run if court decided against him.

Clearly, the court is under the law vested with wide discretion to allow amendment to pleadings of a party at any stage of the proceedings on such terms as may be just, and such amendments shall be made as may be necessary for the purpose of determining the real question in controversy between the parties, and to avoid multiplicity of proceedings.

The Supreme Court set out guiding principles for amendment of pleadings in Gaso Transporter Services Ltd. vs. Martin Adala Obene, SCCA No.4 of 1994 and in so doing cited others cases such as Mulowoza & Brothers Ltd vs. N. Shah & Co. Ltd SCCA No. 26 of 2010 to the effect that an amendment should not occasion injustice to the opposite party and should be granted if it is in the interest of justice and to avoid multiplicity of suits and that It should be made in good faith and that it must not be expressly or impliedly prohibited by law.

Personally do not see where Kyagulanyi went beyond the foregoing guiding principles as his Lawyers were fully aware that a Court will not exercise its discretion to allow an amendment which substitutes a distinctive cause of action for another to change by means of amendment. The argument that the Petitioner had been put under house arrest is not new as the same argument had been raised by Besigye in 2006 and 2011; the court simply poured cold water on it

Thus a party generally encounters little or no difficulty in obtaining leave to amend his/her/its pleadings but the application should not be left to a stage so late in the proceedings which if allowed would prejudice the opposite party and occasioning injustice. It is also the settled that the prejudice is not considered as occasioning any injustice to the opposite party if it is of such a nature that it can be atoned for with costs as was decided Mohan Musisi Kiwanuka vs. Asha Claud, SCCA No. 14 of 2002. It ought to be emphasized that in all circumstances the onus of proving that the prejudice occasioned by the amendment to pleadings cannot be atoned for in costs is on the party seeking to block the amendment.

The rationale of the above stated principles was set earlier in the case of Copper vs. Smith [1884] 26 CHD 700 where Bowen L.J. observed that;

“I think is well established principle that the object of courts is to decide the rights of the parties, and not to punish them for mistakes they make in the conduct of their cases by deciding otherwise then in accordance with their sights…. I know of no kind of error or mistake which, if not fraudulent or intended to outreach, the court ought to correct, if it can be done without injustice to the other party – courts do not exist for the sake of discipline, but for the sake of deciding matters in controversy.

Odgers on Pleadings and Practice 23rd Edition 1991 provides that where the action has been brought on a substantial cause of action for which a good defence has been pleaded, the plaintiff will not be allowed to amend his claim by including it. Therefore it is clear that the law is flexible enough to allow parties to rectify errors in their pleadings however it is also strict to avoid the manipulation of the process by the litigants.

In the year 2009, Section 59(6)(a) of the Presidential Elections Act was challenged in the Constitutional Court by Rtd Col Kiza Besigye on the basis that the Supreme court can only annul an election if the non compliance to the law is such that it affected the outcome in a substantial manner. All five justices dismissed the petition. In their findings, the justices said the substantiality test was not inconsistent with the Constitution because parliament was allowed to make laws that determine circumstances under which an election can be annulled.

The Justices were again quick to remind us that that the Presidency being the highest office in the country, every presidential contestant would run to court for redress which would have a bearing on the political and economic stability of the country. Then what is the purpose of democracy if economic fears override and curtail its implementation of democratic field.

The Justices further argued that doing away with Section 59(6) (a) would mean lowering the standard of proof of presidential election petitions and any slight form of non-compliance would be argued to be sufficient to annul presidential elections. I personally want to agree with the words of Rtd Col Kizza Besigye that the 2016 decision of the Supreme Court practically made it impossible for any aggrieved party to successfully challenge a presidential petition. Indeed Besigye’s fears came to pass in the Petition filed by Amama Mbabazi against the Electoral Commission and Museveni in 2016 Presidential election.

Other than Justice Prof Lillian Tibatemwa-Ekirikubinza, the rest of the nine justices of the Supreme Court who took part in that ruling will be part of the panel to determine the petition and in my view, the bar is too high and from the look of things, the petition is a foregone conclusion and will only serve to the purpose of endorsing Museveni next term as being legitimate despite all the hurdles faced by his opponents before, during and after elections.

I rest my case as;

The writer, Rogers Wadafa is a Lawyer, Researcher and a politician.